Characterizing commitment as an involuntary psychiatric emergency detention that possibly extends into a longer-term detention, the authors aimed to calculate population rates of detentions and chart interstate differences since 2011 by means of publicly available state counts.

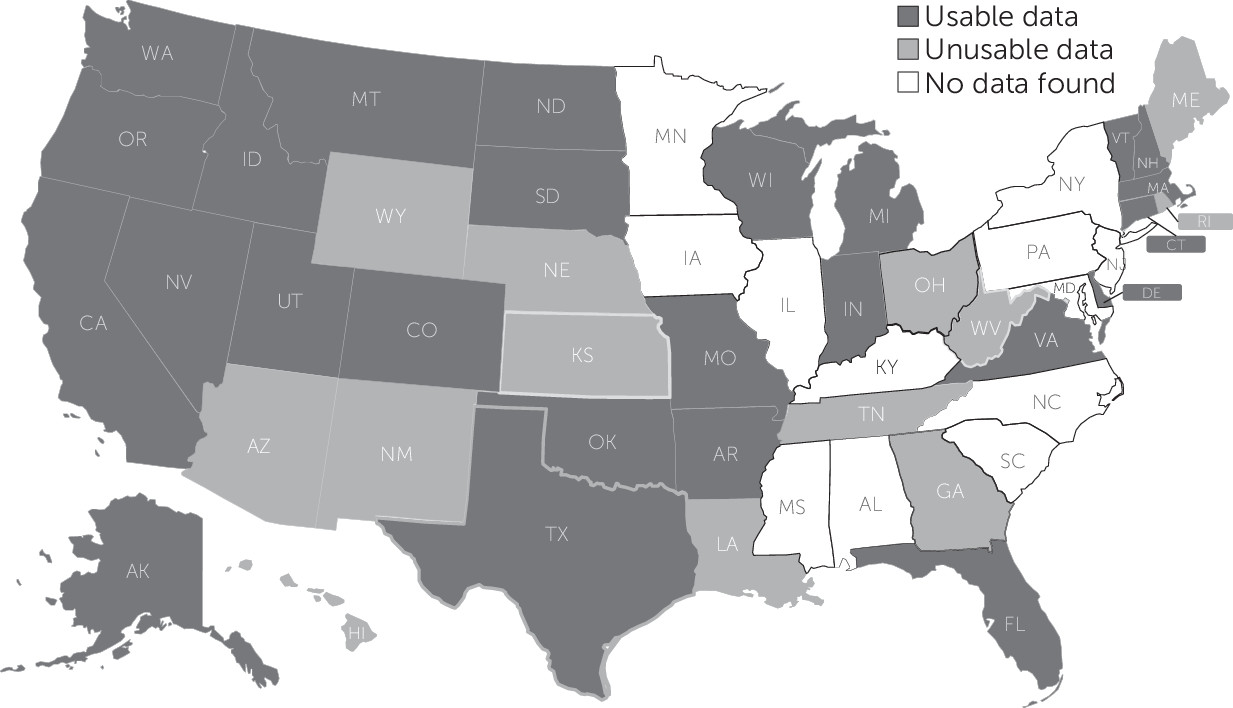

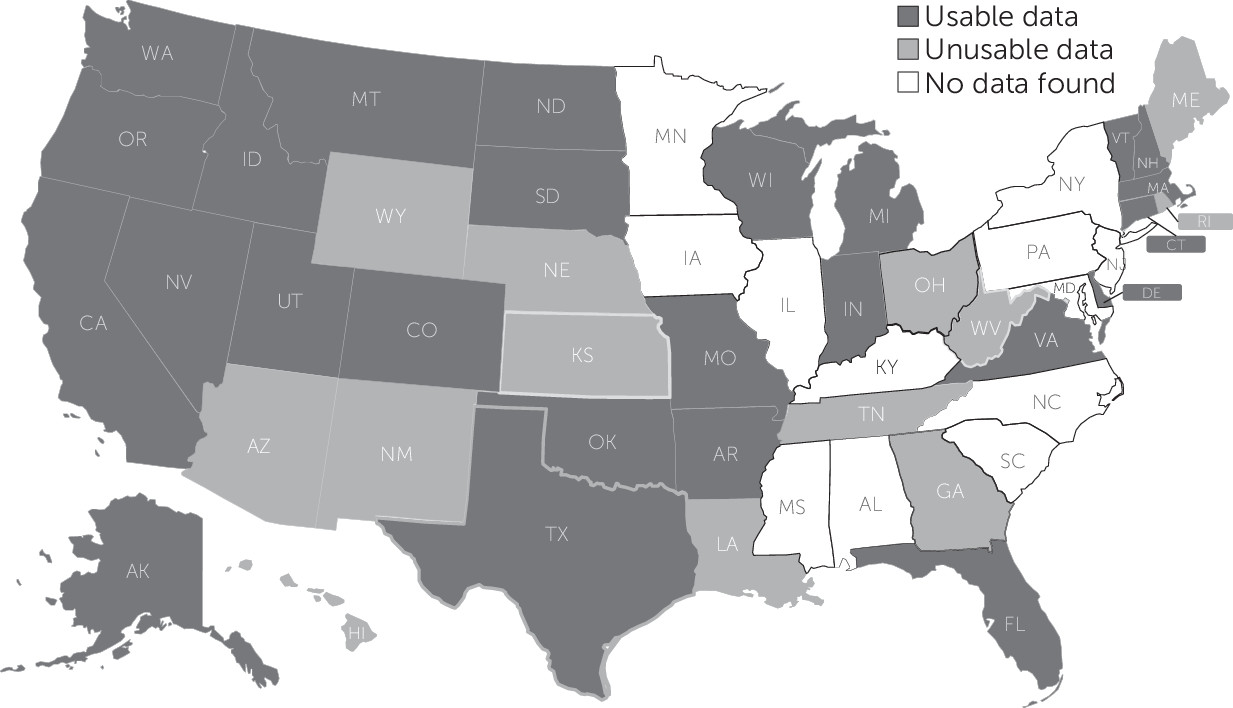

Searches of state health and court websites yielded counts from 38 U.S. states. Usable counts from 25 states were classified as emergency or longer-term detentions and converted to crude rates per 100,000 people by using Census Bureau figures.

All-ages rates (per 100,000 people) of emergency detentions ranged from 29 in Connecticut to 966 in Florida. In 22 states with continuous 2012–2016 data, the average rate increased from 273 to 309. In four of five states with separate counts for adults and minors, rates over time for both were nearly parallel. In eight states that provided relevant data, the mean longer-term detention rate was 42% of a state’s average emergency detention rate. Only one state provided length-of-stay data, and one counted both detentions and persons detained. In 24 states—accounting for 51.9% of the U.S. population—591,402 emergency involuntary detentions were recorded in 2014, the most recent year with most states reporting, a crude rate of 357 per 100,000.

Incidences of involuntary psychiatric detentions between 2011 and 2018 varied 33-fold across 25 states, and the mean state rate increased by three times the mean state population increase. Omissions in most states’ counts clouded interpretation. More valid incidences obtained from standardized national data would improve analysis of the controversial yet opaque procedure of involuntary inpatient civil commitment.

The usability of counts varied (Table 1); 15 did not distinguish between shorter- and longer-term detentions, so we treated them as emergency only, and 17 did not specify to which age group (adults or minors) their counts applied, so we used United States Census Bureau (33) total-population estimates rather than age-specific estimates to compute yearly crude rates of detentions by state, as follows:

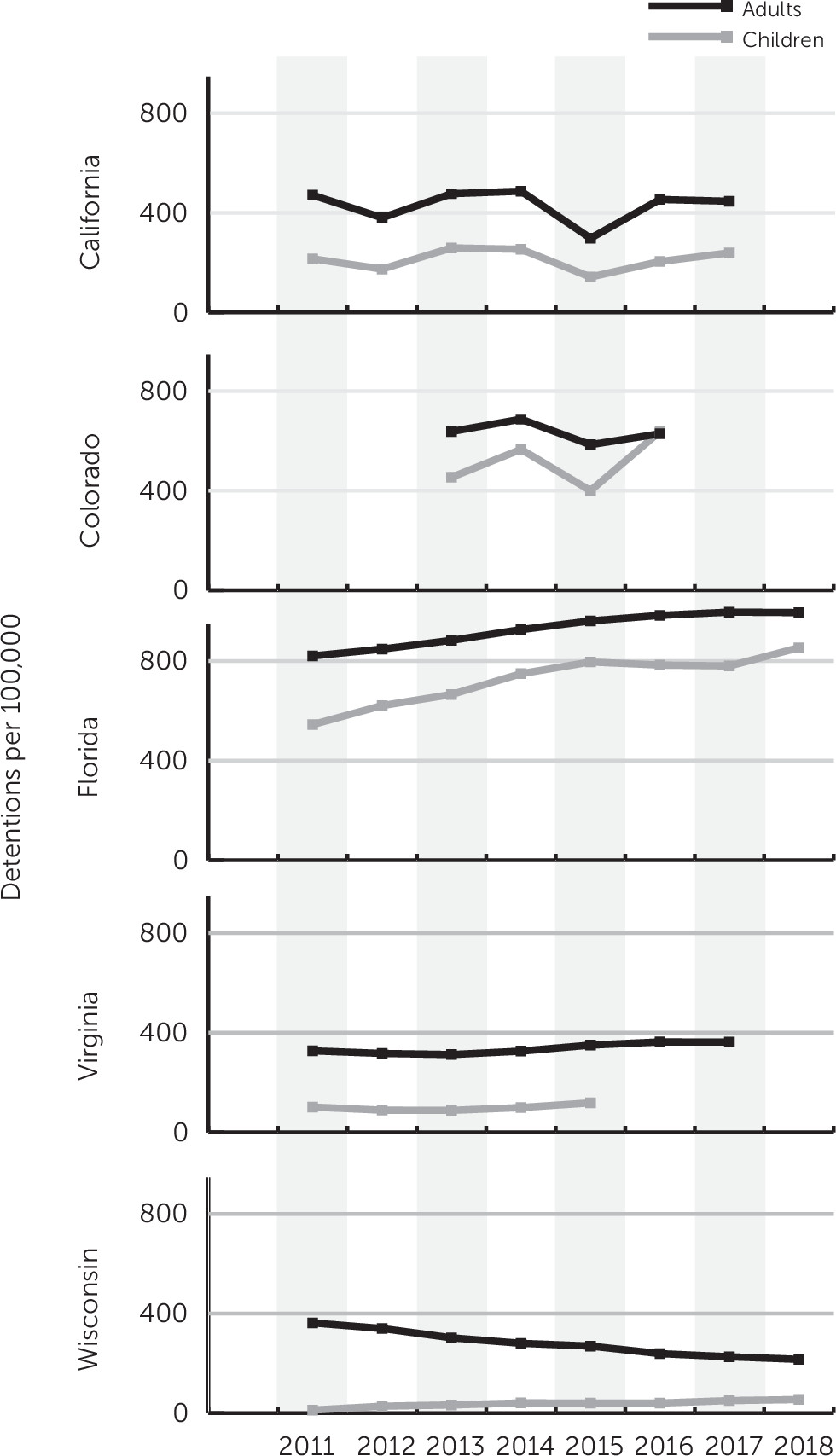

Of 22 states with 6 or more years of data, 15 had a net count increase between the first and last year (mean 50.5%, range 0.6%–139.2%), and seven had a decrease (−17.4%, range −0.4% to −68.5%). When we removed outliers, increases averaged 27.3% (range 9.1%–88.6%) and decreases averaged −3.8% (range −0.4% to −8.1%). States with count increases and those with count decreases both experienced population increases, averaging 5.3% and 4.8%, respectively. The largest count increases were in Nevada (139.2%) and Indiana (102.7%) over 8 years and in Colorado (88.6%) over 6 years. The largest decreases were in Delaware (−68.5%) and Wisconsin (−34.7%). Figure 3 shows that in four of five states providing separate counts of emergency detentions for adults and children, rates for both groups showed nearly parallel lines over the study period.

Only eight states provided counts of longer-term detentions. Figure 4 shows that, between 2011 and 2018, all-ages state rates per 100,000 people ranged from a low of 18 in Oklahoma to a high of 204 in California. We calculated mean annual state rates per 100,000 people, which ranged from lows of 25 and 27 (Oklahoma and Missouri, respectively) to highs of 158 and 159 (Virginia and California, respectively). These longer-term rates were, on average, 42.2% of a state’s mean emergency detention rate during the same period (median 38.9% and range 13% in Missouri to 107.9% in Vermont). Only Vermont reported LOS data: from 2011 to 2018, mean LOS for longer-term “adult involuntary stays” ranged from 35 to 48 days (median 18–21 days).

Finally, only Colorado reported separate counts of detentions and persons detained; from 2012 to 2016, a mean of 89.9% of all-ages emergency detentions (range 88.3%–91.7%) and 81.2% of longer-term detentions (range 68.8%–87.8%) represented unique persons. On request, Florida provided us with estimates of unique persons: a mean of 78% per year from 2010 to 2016 (range 78%–79%) of counts of all-ages emergency detentions (personal communication, Annette Christy, Ph.D., Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Baker Act Reporting Center, August 29, 2018). Thus, during the years surveyed, on average 10% and 22% of persons subjected to emergency detentions in Colorado and Florida, respectively, were held more than once.

In 2014, the most recent year with the most reported counts, 24 states—with a combined population of 165.4 million people (51.9% of the U.S. population)—recorded a total of 591,402 detentions that we classified as all-ages emergency detentions (a crude overall rate of 357.4 per 100,000). Five states, which accounted for 59.2% of the 24 states’ combined populations (Florida, California, Massachusetts, Texas, and Colorado), accounted for 79.8% of the detentions.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first present-day estimates of involuntary psychiatric detentions in the United States based on publicly available data from the largest sample of states in the literature. In 2016, among 22 states, the median and mean emergency detention rates were 196 and 309 per 100,000 people, respectively. Between 2011 and 2018, across 25 states, all-ages emergency detention rates per 100,000 people ranged from 29 in Connecticut to 966 in Florida (a 33-fold variation). Of 22 states with ≥6 years of data, 15 showed a net count increase between the first and last year, and seven showed a decrease. Of eight states that provided counts of longer-term involuntary hospitalizations, all-ages rates per 100,000 people ranged from 18 in Oklahoma to 204 in California. The validity of these estimates, however, is weakened by the study’s limitations discussed in the following.

It is difficult to count civil commitments across states because definitions and mandates for commitment differ among states. The tallying was further complicated by too little accompanying information about the length of any detentions. The data fit the simplest typology of an initial detention that may extend into a longer-term detention, but the data (especially from courts) allowed no finer distinctions. We therefore treated unknown numbers of detentions extended for unknown durations as “at least emergency” detentions. Also, because courts rarely specified whether they counted adults, children, or both, our use of total-population denominators in these cases likely underestimated the incidence of involuntary psychiatric detentions. A few states had both court and DMH counts, but these were discrepant. In these cases, we selected the DMH data because they were better defined. Selecting only court data for consistency would have yielded a different sample of states and different population rates.

The dearth of case definitions and dispositions and our unfamiliarity with individual state practices strained our ability to interpret the data and to address sources of error—such as whether a state’s counts included detentions at nonstate or private facilities, which only a small number of states specified. For example, Colorado’s recent Senate Bill 17-207 mandates health care facilities “not designated” to receive emergency detentions to start reporting these detentions (previously excluded from Colorado’s counts). Its Office of Behavioral Health, responding to an open records request, documented that from May through December 2018, a total of 18,701 involuntary 72-hour holds—56% of which were extended to “continued involuntary treatment”—occurred in 75 “nondesignated facilities.” These concealed detentions would substantially increase the Colorado rates reported in this study.

The issue of privileged access to more complete data than are available on official websites deserves mention. We obtained unpublished data from two states, and our literature search found three studies that analyzed publicly unavailable data that researchers obtained because of privileged relationships with a state DMH and court system (14, 21, 32). Other examples probably exist. This suggests that possibly better-quality incidence or prevalence data are available to some researchers, although we did not find these data used widely in the literature.

Because 24 of the 25 states included in this study provided no LOS data, it remains unknown whether there is a “mismatch” (8) between the statutory timelines for involuntary hospitalizations and the relatively brief mean duration of psychiatric inpatient stays nationally (reported without attention to legal status), which was, for adults, 6.6 days in 2012 and 6.8 days in 2014 (34, 35). Mean rates of longer-term detentions across eight states varied about sixfold and suggested that, on average, about 40% of initial detentions were extended to last anywhere from 2 weeks to 2 years. Only population-based data on the duration of any type of psychiatric detention will clarify the issues.

Despite a dissimilar incidence of emergency detentions of adults and children in the five states with relevant data, in four states the rates for adults and minors followed nearly identical trajectories over the years observed (except for a state that did not distinguish between emergency and longer detentions). The paucity of studies reporting or analyzing rates of civil commitment of youths impedes interpretation of this counterintuitive finding. If not an artifact, the relationship suggests that strong nationwide factors uniformly influence the commitment of both adults and minors.

During our review, we found three relevant national databases and reports. First, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ National Research Institute (NRI) listed, without reliability checks, numbers of emergency holds or longer commitments from 18 and 37 states in 2013 and 2015, respectively (36, 37), taken from a survey distributed to directors of states’ behavioral agencies. For 2015, in nine states for which NRI and this study shared emergency detention counts, NRI’s total was 190,000, whereas our study’s total was 290,000. This large difference could result from the NRI respondents’ inconsistent inclusion of commitments to private facilities and apparent omission of court records. Second, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) receives states’ data on persons “adjudicated as a mental defective” or “committed to a mental institution,” who are prohibited from buying firearms under the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 (38). As of January 31, 2020, NICS had 6,065,302 active “adjudicated mental health” records (39), but these do not separate “adjudications” from “commitments” or give dates for either. Third, 1-day point prevalence estimates of inpatients according to legal status were collected by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration during recent surveys of all known mental health facilities. On April 29 of 2014 and April 30 of 2016, a total of 34,816 and 40,688 individuals, respectively, classified as “nonforensic involuntary” made up 34.4% and 38.4%, respectively, of the total U.S. psychiatric inpatient population (40, 41), but percentages of patient mix cannot be used to derive annual estimates of commitment frequency. In summary, these three national sources did not permit us to reach valid conclusions about the annual incidence of civil commitment in the United States.

We calculated a 22-state mean incidence range of emergency detentions of 273 per 100,000 people in 2012 and 309 per 100,000 in 2016. A recent international comparative study found that rates of “involuntary hospitalization” per 100,000 people in 22 countries across Europe, Australia, and New Zealand in 2015 varied 20-fold, from 14.5 in Italy to 282 in Austria. Thirteen countries experienced an average annual percentage increase between 2008 and 2017, and five experienced a decrease (four did not provide continuous data) (42). As in the present American interstate study, rates may have comprised both emergency and longer-term commitments in unspecified ways. Increasing rates were observed until the early 2000s in five of eight European countries (43). In England (population about 56 million), a study of civil involuntary detentions in health care facilities under Part II of the Mental Health Act of 1983 (which included emergency detentions lasting up to 3 days only if they were extended to longer-term detentions) found that detentions increased 19%, from about 94 per 100,000 people in 2012–2013 to about 116 per 100,000 in 2015–2016 (44). England’s 2017–2018 statistics specify that 15.4% of persons were detained more than once (45), compared with the 16% average observed for emergency detentions in Colorado and Florida from 2010 to 2016.

In terms of clear definitions and adequate details, England’s annual reports on the Mental Health Act of 1983 do not differ substantially from the reports of some American states, notably Colorado, Florida, Virginia, and Vermont, on their own commitments. (Data from California, Texas, and Missouri were detailed but required more effort to interpret.) However, all these U.S. state reports, unlike England’s, generally contain little to no information on case dispositions, missing data, sources of error, and results of efforts to improve data collection and validity. We did not inquire about whether DMH data are produced pursuant to specific departmental customs, legislative mandates, or other directives, representing an area for future research. Court data, embedded within annual reports of court activities and statistics, generally had no commentary.

The discretionary rather than mandatory nature of commitment laws (i.e., an individual who meets a state’s commitment criteria may or may not be committed) reflects society’s ambivalence toward coerced care, and professionals and laypersons readily admit their mixed feelings on the subject (2). The vague way that many sources defined their counts may also reflect this ambivalence. However, from whatever ethical angle one views commitment, it has profound implications for society (2, 28, 46). Therefore, state and private agencies, lay and professional groups, and independent researchers should shed more light on involuntary psychiatric detentions, their correlates, and their outcomes.

Our findings imply that for the near future it will remain difficult to study inpatient commitment empirically, except in single jurisdictions at a time. To assess the broader effects of civil commitment as a primary institutional response to a person’s breakdown seems a more distant prospect. That only a single state reported data on the full length of involuntary detentions seems baffling in this era of electronic records. Why some states report detentions fully whereas others do not publish the simplest aggregate counts should be better understood.

Without accurate incidence estimates, links to potentially contributing and consequent factors of civil commitment cannot be reliably assessed; these include threatened, attempted, and completed suicides (47); substance misuse or other previous commitments; availability of community resources and hospital beds; police involvement; chronic homelessness; economic deprivation (48); publicized mass shootings; and natural disasters. The findings of this study signal the need for a meaningful, nationally standardized data collection approach to produce valid population-based estimates of a major rights-restrictive procedure that mobilizes considerable human, economic, and logistical capital across all behavioral health and justice systems in the United States.

Ms. Lee received partial support from the Graduate Division of the University of California, Los Angeles.